City event studies MLK’s ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’

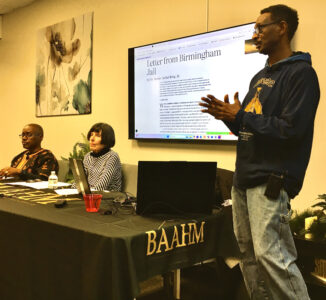

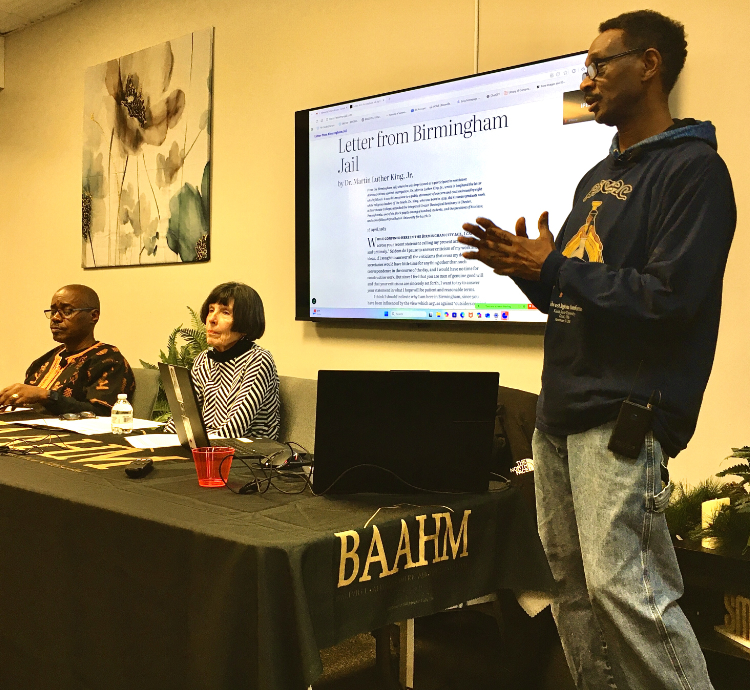

Correspondent photo / Sean Barron Vincent Shivers, a longtime area historian, talks about the importance of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail” during a program Saturday at Triyounity LLC in Warren to remember and honor King’s life and enduring legacy.

WARREN — Solo Ogletree may not know many of the complex intricacies that, woven together, formed the crux of who Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was, but he certainly appears to have the foundation in place.

“He was against segregation and stuff, and he had a dream that whites and blacks could be together,” Solo, 13, of Youngstown, said.

The teen, however, may be understating the extent to which his knowledge of the civil rights icon, Baptist minister and humanitarian stretches. That’s because Solo was among about 23 children and adults who read sections of King’s iconic “Letter from Birmingham Jail” during a reading and panel discussion of the famous document Saturday afternoon at Triyounity Health & Wellness LLC, 239 Main Ave. SW.

Hosting the two-hour program and panel discussion to remember and honor King’s life and legacy was the Braceville African American Heritage Museum, which opened in 2024.

Panelists were Penny Wells, Mahoning Valley Sojourn to the Past’s executive director; Vincent Shivers, a longtime historian; and the Rev. Orneil Heller, assistant pastor with Warren-based New Jerusalem Fellowship Church.

Solo also gleaned a few other life lessons via gaining a deeper understanding of and appreciation for part of King’s priorities.

“More people should follow him — be nice to each other and don’t discriminate,” he added.

On April 12, 1963, which was Good Friday, King was arrested on a charge of defying a court injunction prohibiting anti-segregation protests that were an integral part of direct-action efforts to end segregation in Birmingham — which, many historians and others have contended, was the nation’s most segregated city. While spending eight days in solitary confinement, and without access to full sheets of paper or other writing materials, King penned much of the letter on pieces of newspaper margins each day and had his lawyer, Clarence Jones, smuggle the correspondence out of the jail to be assembled — much like a jigsaw puzzle.

Once the scraps were safely out, they were handed to Wyatt Tee Walker, a king confidante, who took them to be sorted out, Wells noted. A remarkable gift King had was being able to write it so eloquently and be able to pick up each day where he had left off, she said.

The essence of the letter highlighted the moral necessity and need for nonviolent civil disobedience to be used against unjust laws and segregation, and that everyone had an obligation to fight such wrongs. The letter also criticized eight white moderate clergy members who did not oppose civil rights, but took the position that such demonstrations were unwise and untimely, and should be dealt with patiently and through the courts. The eight powerful religious leaders King criticized in his letter for their stance were the Alabama Catholic bishop and auxiliary bishop, two Alabama Methodist bishops, a local rabbi, the Alabama Presbytery moderator of the Presbyterian Church, the Alabama Episcopal bishop and First Baptist Church of Birmingham’s lead pastor, Wells noted.

She added that the peaceful protests and boycotts, to a significant degree, targeted many of downtown Birmingham’s businesses that discriminated against blacks. The actions coincided with the Easter holiday, which was the busiest shopping time of the year and would hurt the merchants economically, Wells explained, adding that dozens of bombings of black homes occurred in Birmingham, earning the city the unflattering sobriquet, “Bombingham.”

“His letter, written at a decisive moment in his leadership, written without access to his bookshelf and without the help of his frequent collaborators, would become his most passionate and lasting prose,” Jonathan Eig wrote in his 2023 book “King: A Life.” “He called upon the masterpieces of philosophy and theology he had learned at Crozer (Theological Seminary in Chester, Pa.) and Boston University. … Going to jail inspired King to preach and to protest, to write with a fervor that seldom appeared in his prose and, in the process, to redefine American religious leadership.”

In the 1998 book “The Autobiography of Martin Luther King Jr.,” published posthumously by Clayborne Carson, King describes the letter writing process himself: “I didn’t have anything at my disposal like a pad or writing paper. Begun in the margins of the newspaper in which the statement (from the eight clergymen) appeared, the letter was continued on scraps of writing paper supplied by a friendly Negro trusty and concluded on a pad my attorneys were eventually permitted to leave me. I was able to slip it out of the jail to one of my assistants through the lawyer.”

Among the recurring themes that courses through the lengthy letter is what King saw as the inherent value of nonviolent direct action campaigns to correct societal injustices.

“You may well ask, ‘Why direct action? Why sit-ins, marches and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?’ You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks to so dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored,” he wrote. “My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent resistor may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word ‘tension.’ I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth.”

During the May 1963 Children’s Crusade to desegregate Birmingham — resulting in the arrests of an estimated 4,000 young people in and around Kelly Ingram Park for marching without a permit — King was instrumental in working behind the scenes to secure an agreement with city leaders to end segregation, Wells said. Beforehand, the Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth, the fiery pastor of Bethel Baptist Church and founder in 1958 of a civil rights organization called the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, invited King to help in the struggle Shuttlesworth had been nonviolently fighting for years, she continued.

After everyone read their parts of the letter, a discussion ensued in which several readers drew parallels between the struggles regarding the mistreatment of mainly blacks in 1963 in the Jim Crow era and how King and others fought to address and correct such injustices, with many of today’s societal problems. Perhaps a most compelling example, Wells said, can be found in how Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents are mistreating and terrorizing American citizens as well as immigrants in Minneapolis and elsewhere — coupled with the Donald Trump administration giving it legal status — and much of how the Nazis’ treatment of Jews was sanctioned.

Adding to the problem is that today, as then, too many people remain on the sidelines as silent witnesses, Wells said.

In the Letter from Birmingham Jail, King makes a compelling case of comparison that several of the readers said is tragically applicable in 2026.

“We should never forget that everything Adolph Hitler did in Germany was ‘legal’ and everything the Hungarian freedom fighters did in Hungary was ‘illegal,'” King wrote. “It was ‘illegal’ to aid and comfort a Jew in Hitler’s Germany.

“I had hoped the white moderate would understand that law and order exist for the purpose of establishing justice and that when they fail in this purpose, they become the dangerously structured dams that block the flow of social progress. … Actually, we who engage in nonviolent direct action are not the creators of tension,” King continued. “We merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive. We bring it out in the open, where it can be seen and dealt with. Like a boil that can never be cured so long as it is covered up but must be opened, with all its ugliness, to the natural medicines of air and light, injustice must be exposed, with all the tension its exposure creates, to the light of human conscience and the air of national opinion before it can be cured.”

An enormous challenge today is the easy and deliberate dissemination of misinformation on social media platforms, a result of which often is making it so that many people caught up in such a web reflexively draw conclusions before being fully aware of the facts, Shivers said.

“We have to start using facts over emotions,” he said.

Shivers added that even though King wrote the letter in April, the reading took place Saturday to honor the civil rights icon a bit differently. Too often, he is viewed as one-dimensional, merely as someone who had a dream but with no deeper contextualization, Shivers said.