Cortland Army veteran also a published author

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is part of a weekly series highlighting local veterans that runs every Monday through Veterans Day. To suggest a veteran, call Metro Editor Marly Reichert at 330-841-1737 or email her at mreichert@tribtoday.com.

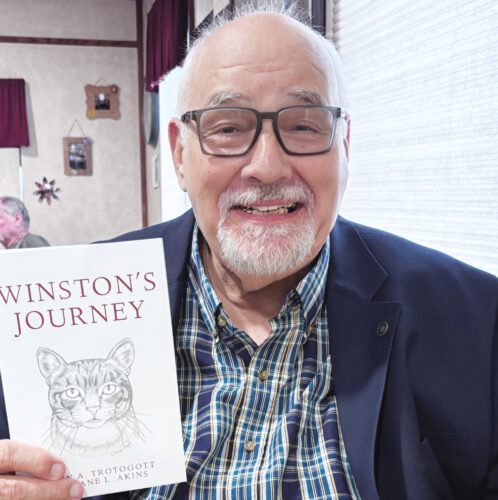

Correspondent photo / Melissa Channell

John Trotogott, 79, of Cortland, a native of Champion, served in the Army during the Vietnam War. After retiring and while still living in Portland, Oregon, he and his mentor wrote this book.

Enamored with helicopters at the time partly because of seeing the movie “Saigon,” Trotogott was sure he wanted to be a pilot. The recruiter asked him “when you go to flight school, if you drop out, or fail, or whatever, what do you want to do?” Trotogott answered, “just give me a helicopter repair class. I just want to be around helicopters.”

Trotogott headed to Cleveland to take the qualifying tests.

“On the IQ test, I just hit the minimum and my mother, a jokester, said, ‘I bet they boosted that up a little bit to get more people.’ The last test was for color blindness and I’m colorblind,” Trotogott said, noting his dream of being a helicopter pilot was dashed.

The Army recruiter began detailing what Trotogott would be doing by saying “‘you’re going to go here, and there, and Germany, and Virginia,” at which point Trotogott questioned “how can I do that in 24 months?”

Typically, a drafted individual was only required to serve for two years, but when Trotogott chose flight school, the paperwork he signed actually signed him up for three years.

He went to basic training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, then went to Advanced Individual Training at Fort Eustis, Virginia. It was a transportation outfit with a helicopter unit and is where he trained to work on helicopters.

During down time he played fast-pitch softball and threw javelin for the teams there. At one point while practicing, he met a recruit named Carl who expressed an interest in the javelin throwing. This led to Trotogott mentoring Carl, helping him to improve his reading and writing, being a friend to him and standing up for him when he was about to be passed over for his private first class rank.

“I went to see the executive officer. I explained that Carl performed an official job with a written description. I must have won the argument, because four days later, Carl received his PFC orders, along with a raise. His face shone with pride. I never told him that I advocated for him,” Trotogott said.

After his training, Trotogott was chosen for the honor guard.

Trotogott’s first assignment was with the 335th assault helicopter company but when he arrived, he found that the helicopter he was trained to repair had been replaced and he was suddenly without a specific job. This meant hanging around the room where all the medics waited, filing paperwork and helping as he was able.

One day, specialist Louis T. Jones, a towering Hawaiian medic from the 25th medical attachment, called out, “Hey, don’t just watch! Help me. You don’t have a job, so wanna come along?”

That led to Trotogott working for the Medical Civil Action Program, which involved visiting villages and refugee camps to teach sanitation and midwifery, perform minor dental work, distribute tools and clothing, and treat the sick.

The day after he joined the MCAP, one of the flight surgeons asked if Trotogott would like to become a medic, explaining that since he was without an assigned job he would soon be sent elsewhere, including the possibility of combat.

“Yes, sir, I’d love to be a medic, I said. My lifeguard first aid training paled in comparison to the skills required of a field medic — administering shots, drawing blood and inserting IVs. Keeping everything sterile in a dusty dispensary tent or outdoors, surrounded by dirt, grease and oil, was a constant challenge. I swabbed areas with alcohol or iodine, often without soap or water,” Trotogott said.

Traveling in a helicopter and learning on the job provided excitement.

“As we moved north, I continued learning from my team and assisting hospitals. With 17 EVAC hospitals in Vietnam, no soldier was more than 40 minutes from care. I seized every chance for on-the-job training, honing my ability to think and act quickly under pressure. Beyond medical duties, I learned to operate a machine gun, occasionally serving as a door gunner or crew chief to relieve others,” he said.

At one outpost a local man was hired to do repair work on the buildings, but he died one night attempting to breach the perimeter.

“We later learned he’d mapped our base for rocket and mortar attacks while working among us,” Trotogott said.

Just a few weeks before, Trotogott had been to the man’s house to treat his son.

“Realizing I’d been in an enemy’s house sent a chill down my spine,” he said.

Another incident occurred while riding in a convoy truck with new infantry troops.

“I saw one knock an elderly Vietnamese man off his bicycle. Furious, I pinned the soldier down yelling, ‘We’re not here for this!’ His friends’ angry glares made me grip my pistol for the rest of the ride, but no one acted,” Trotogott said.

He also worked with some groups handing out donations of clothing and other supplies donated from the U.S.

After his time in the Army, Trotogott worked at Republic Steel and attended Youngstown State University. After about 10 years, a desire for the Midwest (an uncle lived in that area) led Trotogott and his wife Mary Nora to go west. First, a job led them to Nevada, where Trotogott worked as a millwright at a titanium plant, got his associate degree in the arts and initiated and helped construct a curriculum for maintenance people, electricians and welders, and millwrights.

They married in Vancouver Washington and lived in Portland, Oregon, which was right across the river, for 33 years. He eventually ended up in industrial sales, and his wife worked for a nonprofit.

Once they retired they decided to return to Trumbull County about a year and a half ago to a senior community in the Cortland area.

He is an author and had two pieces of writing published in a book called “Word Explosion.” He also wrote a book with his mentor called “Winston’s Journey,” which is about a cat he and Mary Nora owned. Both books are available on Amazon.

John Trotogott

AGE: 79

RESIDENCE: Cortland

SERVICE BRANCH: Army

MILITARY HONORS: National Defense Service Medal, Vietnam Service Medal, Vietnam Campaign Medal, Expert / Rifle, Air Medal, Army Combat Badge, Army Reserve Components Achievement Medal

OCCUPATION: Retired steelworker and industrial salesman

FAMILY: wife, Mary Nora