Former Howland man Glenn Luther strives to rescue Afghan journalists

Howland native strives to rescue Afghan journalists

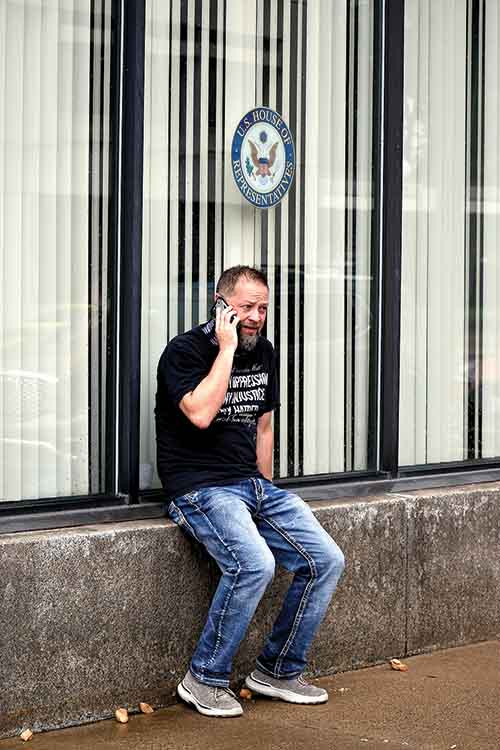

Staff photo / Renee Fox Glenn Luther, 42, Laurel, Md., formerly of Howland, came to town to implore U.S. Rep. Tim Ryan, D-Howland, to help 21 people — five of his former Afghan photojournalism students and their families — leave Afghanistan as the Taliban takes over the country, endangering Afghan journalists. Luther was able to contact one of Ryan’s staffers on Tuesday and provide the names of the people he wants to help leave the country. The staffer is working to add their names to “fly-out” lists, but there is no guarantee yet that Luther’s Afghan friends will make it to safety.

WARREN — Glenn Luther rushed to Warren from his home in Laurel, Md. — forgetting even to pack socks — as he dropped everything to implore a local congressman to help Afghan journalists get to safety.

They are his former photojournalism students, considered friends, struggling to find a way to flee Afghanistan and realizing the target the profession places on their backs.

Luther, 42, formerly of Howland, went to Afghanistan in 2003 to teach aspiring Afghan journalists, helping to found the country’s first school on the subject. Some students went on to operate the first photo agency in the country run by Afghan people — something Luther helped build.

“They empowered themselves to show the world Afghanistan through their own eyes, not through the eyes of a parachute journalist,” Luther said.

Luther was a senior at Kent State University at the time. Shortly after graduating high school in 1997, Luther worked for both the Tribune Chronicle and The Vindicator, honing the skills professors taught him with staff photographers of the newspapers and the university’s publication.

In Afghanistan, Luther made lifelong friends and the students built reputations as fearless and successful journalists. One man won a Pulitzer prize, others won prizes from other top news organizations, and published in well-circulated, national magazines and other outlets.

‘GET OUT’

But as the Taliban started to take back the ground the U.S. and Afghan government officials once secured, the danger started to become obvious, and Luther started inquiring about how his friends would make it out.

“I told them, ‘You need to get out.’ And they were like, ‘The roads are blocked, we can’t. It is only through air,'” Luther said.

Images coming in from the country show people Monday trying to hold onto the outside of airplanes leaving the airfield in Kabul, desperate to flee. Those without passports had that extra step to worry about before they could look for seats on airplanes for themselves and family members.

“Because all these capitals were falling, people were flooding into Kabul as the last safe place to be, and they were also in line trying to get passports,” Luther said. The lines for the passport office lasted all day, and the wait wasn’t fruitful for Luther’s contacts, who never reached the front of the line before the office closed each day.

Before the Taliban flooded into Kabul, Luther was looking for ways to help his friends get out as cities fell quickly after the U.S. pulled out of Afghanistan, turning out the lights at Bagram Airfield and leaving behind much of the equipment shipped to aid allies in the war effort.

Luther realized he had the means to pay for tickets and visas for his five friends and their families.

“At those prices, I could use my credit card. I could do this; I could save them all. Everything was going great. I had a plan and I felt relief,” he said.

But then, the prices started rising.

“This whole process has been waves, waves of hope and peace, and then waves of terror and fear. It’s an ocean I just want to be still,” Luther said.

Soon, prices weren’t the only barrier to Luther’s friends and other Afghans intent on fleeing the Taliban’s rule, as seats leaving the country were few and far between, Taliban checkpoints were established and it appeared for some time this week that the airport at Kabul might be compromised.

Luther knew he had to do something to help the journalists he helped train.

‘PLEASE HELP US’

“When I first started teaching, my students used to beg, ‘Glenn, take us out of Afghanistan. We don’t want to be here, please help us get out.’ I was their photojournalism teacher. So, I pointed at my camera and I said, ‘This camera will take you everywhere.’ And it has, it’s taken some of them all over the world,” Luther said.

“I feel responsible to be the one who helps them to get out, to find safety, so the stories that they have been telling for the past 20 years can be preserved. And, more selfishly, so that my friends can be safe. But it is important, because the Taliban will wipe out everything. The history of the last 20 years will be destroyed.”

Luther’s contacts are not being named to protect them and their families from retaliation. Their skills in the journalism trade are what make them targets of the Taliban, Luther said.

“The Taliban kept good records. They recorded everything everyone did in hopes of getting retribution. That is why they are sending threats to my students because they saw my students standing up for women’s rights, democracy and a free press,” he said.

REACHING OUT TO RYAN

So Luther dashed Monday evening to Warren, hoping U.S. Rep. Tim Ryan, D-Howland, can do something.

He reached out on social media, calling every staffer he could get a number for. On Tuesday morning, he went to Ryan’s Warren office on West Market Street, hoping to find the congressman and plead his case.

Scheduler and executive assistant Illa Willis gave Luther a contact number for Matthew Vadas, a constituent liaison for Ryan who handles visa issues.

“Time is of the essence,” he told Willis.

He walked out of Ryan’s offices and called Vadas immediately, leaving a voicemail.

“As a journalist, you aim to give a voice to the voiceless and, right now, the voiceless are leaving messages on voicemail boxes, hoping someone listens to them,” Luther said.

While waiting for a return call, Luther fretted.

“I hope that I can find a few extra seats on one of those planes for my students before it is too late. Because, eventually, those planes will stop flying,” he said.

Luther provided the office with the names and information of the 28 people he hopes to help to safety. He also is compiling a list of other journalists he hopes to help.

Not long after, Vadas returned the call to Luther as he paced the newsroom at 240 Franklin St. SE.

“They are working on it; they are going to try to put them all on the fly-out list, which is all I want,” Luther said with tears in his eyes after hanging up the phone.

Luther shared the information with his contacts.

“I think for the first time they have hope. You can see it in their excitement, after weeks of staring at the news and the Taliban closing in, they see a tiny glimmer of hope,” Luther said. “But until they have two feet in a country other than Afghanistan, I don’t think I’ll be able to rest.”