PBS documentary places spotlight on Marion Motley’s legacy

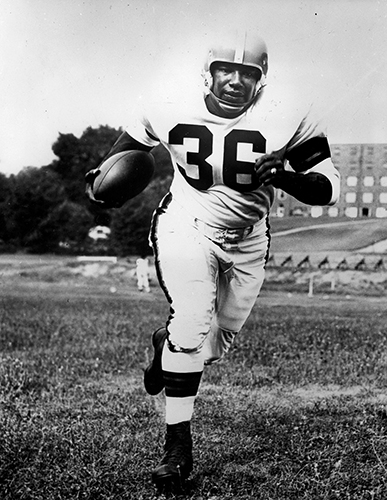

Submitted photo Marion Motley, shown here in a publicity photo from the early 1950s, was one of four black players who integrated professional football in 1946, a year before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball.

Jackie Robinson is famous and celebrated for integrating Major League Baseball in 1947.

Professional football integrated the year before, but the four players who accomplished that feat largely are forgotten.

A half-hour documentary premiering Friday hopes to bring attention to the greatest of those four athletes, Canton native Marion Motley. “Lines Broken: The Story of Marion Motley” will air nine times on PBS Western Reserve and its Fusion channel for Black History Month.

Several people with Mahoning Valley ties are part of the project. Warren native David Lee Morgan Jr. is one of its producers, and Warren G. Harding football announcer James Wells narrates the film. Warren native Paul Warfield, a Hall of Fame inductee for his career as a wide receiver with the Cleveland Browns and Miami Dolphins, is interviewed in the film, and Canton native and one-time Warren resident James Waters II is co-director and a producer on the project.

Motley played eight seasons for the Cleveland Browns in the All-American Football Conference (1946-1949) and the National Football League (1950-1953). The fullback was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1968.

Even though he also was a Canton McKinley High School graduate, Waters said he didn’t really know Motley’s story.

“The biggest thing we wanted to do was share that story, make more people aware of the forgotten four and that one of them came from Canton McKinley,” Waters said.

Each of the people involved used their contacts to bring in potential sources.

“(Co-director / producer) Shaun Horrigan, his dad worked for the Hall of Fame,” Morgan said. “We were able to use him and his influence to get to people. I knew Paul Warfield, and he knew me and my family. We were able to pull from our own professional experiences and brainstormed who we thought would be best to talk to.”

In the documentary, Warfield calls Motley “a superlative player who made great plays for the Cleveland Browns, was an integral part of their winning, and he looked like me.”

Several other Hall of Fame inductees are featured in the half-hour documentary along with members of Motley’s family and Mike Brown, the son of coach Paul Brown. Brown was the football coach at Massillon High School when Motley was a student at Canton. Brown put Motley on the Great Lakes Naval Academy football team he coached during World War II, and he signed Motley and offensive lineman Bill Willis to play for the Brown in ’46.

“You have to give it to Paul Brown,” said Morgan, who now teaches in the same Massillon school district where Brown once coached. “His contributions and what he did, saying if they can play and have good character, they can play for me.”

The other two players who integrated professional football in 1946 were Kenny Washington and Woody Strode with the Los Angeles Rams. Both teams added two black players because the teams couldn’t have a black and a white player room together on the road.

The documentary points out that Motley and the other players endured the same slurs and death threats that greeted Robinson when he was called up by the Brooklyn Dodgers the next year. They also endured physical abuse from opposing players who would commit personal fouls that the referees ignored.

Waters believes Robinson is remembered more than Motley and the other black football players because of when it occurred.

“Football trumps baseball today, but back then baseball was the national pastime, the all-American game,” Waters said. “They didn’t take football as serious, I guess.”

The last couple of minutes of the television special argue Canton should do more to recognize Motley and his important contribution to integrating football. Waters, Horrigan and Morgan would like to expand Motley’s legacy beyond northeast Ohio by expanding “Lines Broken” into a feature-length documentary. That’s how the project originally was conceived.

“We still want to do a longer piece,” Waters said. “The nice thing about partnering with PBS is it allowed us somewhat of a budget. This is a passion project for all us, we’ve been working with no budget, trying to raise money. Working with PBS allowed us to pay back a little of the favors we called in, the camera guys and audio guys who worked for us. Hopefully this creates a little buzz if someone wants to invest (in a full-length documentary).”