Bridge by Steve Becker

There is no denying that in some deals, declarer must guess what to do because he doesn’t know how the adverse cards are divided. Any clues might be disturbingly sparse, or the defense might be exceptionally sharp.

Fortunately, such deals are rare. On most occasions, declarer can find a way to improve his chances of guessing correctly, or can avoid guessing altogether.

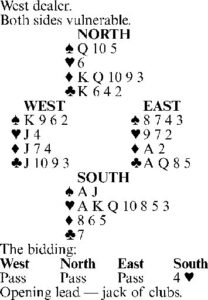

Take this case where South went wrong. He ruffed the second club lead, drew trump and led a diamond to dummy’s queen. East played low, realizing that if he took the ace, his partner’s jack (if he had it) would be subject to a later finesse.

Declarer then led a low spade to his jack. West won with the king and returned a club. South ruffed, cashed the ace of spades and played another diamond, West following low.

South was now in a quandary. If West had started with the J-7-4, the winning play was the ten; if West had started with the A-7-4, the winning play was the king. Either play could turn out right or wrong. In practice, South guessed wrong. He played the king and eventually lost another diamond to go down one.

It is true that South ran into sturdy defense, as well as bad luck. However, his difficulties were self-imposed. He missed a surefire way to make the contract without exposing himself to a guess.

After ruffing the second club and drawing trump, South should have played the A-J of spades, deliberately spurning the spade finesse. This would have assured that when he subsequently got to dummy with the king or queen of diamonds, he could discard his third diamond on the queen of spades, and his only losers would have been a spade, a diamond and a club.

Tomorrow: A critical choice of plays.